Written by Heather Davies-Strickleton, Senior Analytical Scientist

We are not alone in this world. Although we can’t see them, we share our surroundings with billions of tiny microscopic organisms (microbes). Like us, they’re looking for a cosy place to live, survive and thrive. And the place that many of them like to call home is actually us – the human body! While many of these microbes help us, there are some that we could just live without.

Not such a fun guy to have around is a type of microbe called a dermatophyte (from Greek δέρμα derma (skin) and φυτόν phyton “plant”). Dermatophytes are filamentous fungi in the genera of Trichophyton, Microsporum and Epidermophyton, which can invade our skin, hair and nail to cause irritating, highly-infectious rashes (e.g. ringworm and Athlete’s foot), hair loss (e.g. ringworm of the scalp) and flaky, discoloured nails (e.g. fungal nail disease).1

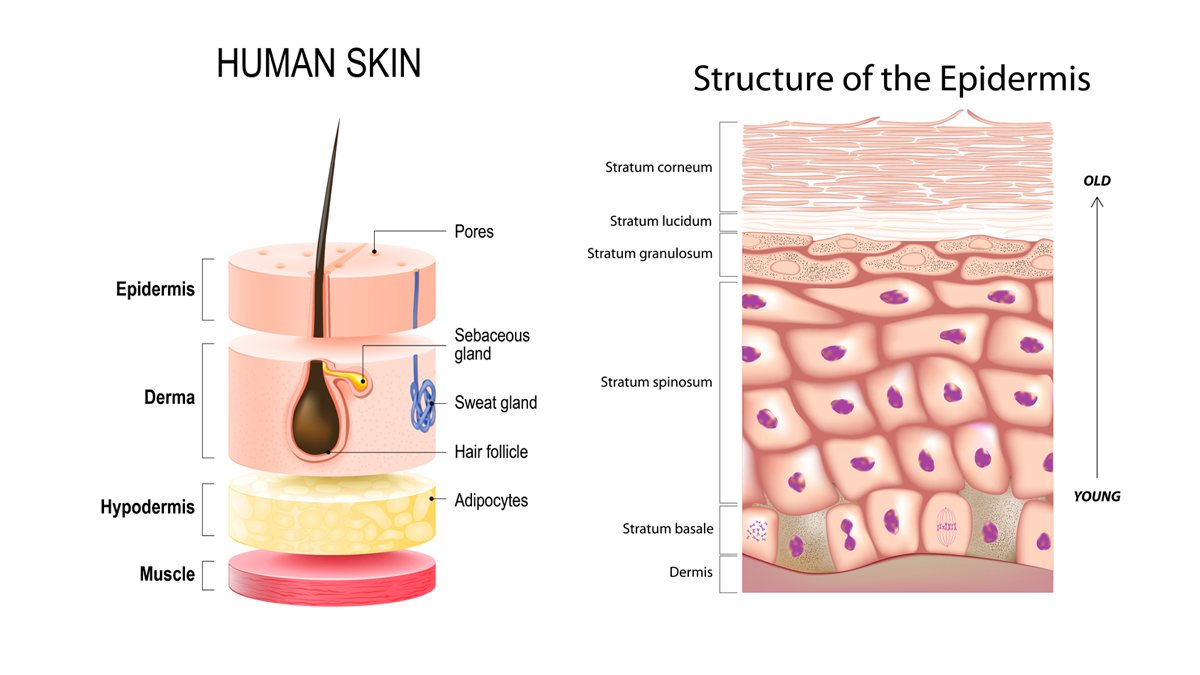

Dermatophytes achieve this because they live off keratin – the tough, fibrous protein important for the structure of skin, hair and nails.1 Within our skin, keratin-making cells are present in the upper layers (the epidermis) and travel upwards over time, becoming rough, dry and flaky, and producing a “dead” layer of cells (called the stratum corneum), which acts as a constantly renewing barrier to the outside world.2 Fortunately, under normal, healthy conditions, this top skin layer is dry and not easily invaded by dermatophytes.

However, the scales can easily be tipped in the favour of fungal growth. Dermatophytes particularly love warm, moist environments, which are often created in our active lifestyles.1 Getting sweaty and hot when playing sports or wearing enclosed footwear can create a haven for dermatophytes to thrive. It is perhaps therefore not surprising that some fungal skin infections are commonly called things like “jock itch” (tinea cruris) and “Athlete’s foot” (tinea pedis)! In addition to our sporting activities and fashion trends, having trauma, metabolic disorders (e.g. diabetes) or weakened immune defence can also create opportunities for fungal infections to take hold.3

When dermatophyte skin infection occurs, fungal spores from the environment that are normally harmlessly attached to the top layers of the skin germinate into tubes called mycelia.4,5 The dermatophytes reach into the upper, keratin-rich layers of the skin (epidermis) by extending long, branched ropes called hyphae.5,6 Here, they release “Pac-man” like proteases that chomp their way through our keratin, breaking it down for nutrients to live on, and make themselves feel at home.5,7

In some cases, dermatophytes can grow into deeper layers of the skin, and cause more serious infections.3 However, usually the fungi stay in the upper layers of the skin, growing outwards into a ring-shaped rash. As a result, some of these infections have the common name of “ringworm” (tinea corporis), even though the culprit is a dermatophyte rather than a worm! Whilst not usually serious, this is usually irritating and itchy, highly embarrassing and something we want to get rid of as quickly as possible. Fortunately, current and emerging anti-fungal drugs can help us to evict these unwanted residents. Anti-fungal creams or tablets can provide the medical means to specifically attack fungal cells, whilst leaving our own cells intact, relieving us from the irritation and embarrassment of the mouldy microbes we don’t want under our skin.8

References

- American Family Physician. Dermatophyte Infections. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/afp/2003/0101/p101.html [accessed on 28/02/2020].

- Verywell Health. What Cell Turnover Is and How It Relates to Acne Development. Available from: https://www.verywellhealth.com/cell-turnover-15552 [accessed on 28/02/2020].

- Rouzard C, Hay R, Chosidow O et al. Journal of Fungi (Basel). Severe Dermatophytosis and Acquired or Innate Immunodeficiency: A Review. 2016; 2(1): 4.

- Science Direct. Spore Germination. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/spore-germination [accessed on 28/02/2020].

- Vermout S, Tabart J, Baldo A et al. Mycopathologia. Pathogeneis of Dermatophytosis. 2008: 166: 267-275

- Jensen J-M, Pfeiffer S, Alaki T et al. Journal of Investigative Medicine. Barrier Function, Epidermal Differentiation, and Human β-Defensin 2 Expression in Tinea Corporis. 2007: 127(7): 1720-7.

- Kaufman G, Horwitz BA, Duek L et al. Medical Mycology. Infection stages of the dermatophyte pathogen Trichophyton: microscopic characterization and proteolytic enzymes. 2007; 45: 149-155.

- Centers for disease control and prevention. Fungal diseases. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/ringworm/treatment.html [Accessed on 11/10/2019]